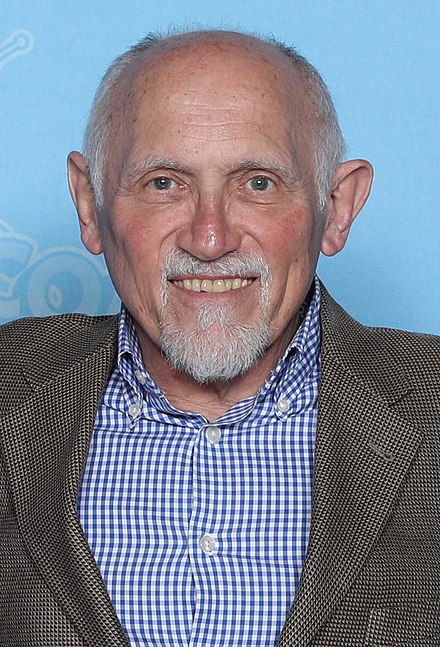

Acting is more than a talent, it is also an aesthetic technology. I had never looked at the art of the thespian in that way, not until I recently attended a webinar titled Masterclass: Shakespeare’s Rhetoric with Armin Shimerman, conducted by actor and Shakespearean expert, Armin Shimerman and sponsored by the Antaeus Theatre Company of Glendale.

I once read in an interview with the late award-winning actor George C. Scott indicating that he thought acting a Shakespeare character was the simplest of all the roles an actor could perform. Mr.Scott suggested that it was all on the page and that the actor just had to emphasize the right word or words for the meaning of the text to become apparent. The implication being that there was no need to ponder subtext; it was evident on the page. That contention has long been confusing to me, but Mr. Shimerman’s webinar clarified the point that George C. made.

Shakespeare’s theater was based on a rhetorical theatricality, according to Mr. Shimerman’s lecture and helpful glossary of terms (that came as an attachment to the webinar’s Zoom link). Rhetorical theatricality, “is a system of thought that Elizabethan era writers were preoccupied with. Further, it is the artistic use of words and ideas to make a logistic point. Language is the soul as well as the outward trappings of Shakespeare’s writings.”

There are a trio of rhetorical appeals: Logos (logic) which is a primary appeal in the Elizabethan era and represented in Shakespeare’s writing. A clue to the employment of logos are terms such as “then,” “therefore,” “since,” or “thus.” These words are often used as a prelude to a logical appeal.

Ethos is another rhetorical appeal. Employing this ethical appeal “the character,” according to Mr. Shimerman, “demonstrates the honor or righteousness or nobility or wisdom of him/herself or of another character he is defending.” Moreover, “by extolling to the listener(s) these virtues, the listener(s) believe the value of what the meritorious person has said.”

Pathos is the third rhetorical appeal. Using a pathetic appeal “the character demonstrates, through heartfelt emotions, the truthfulness of what he/she is saying. The listener feels for the speaker and, therefore, believes what is being said.”

Of this intriguing trio of rhetorical approaches, Mr. Shimerman asserts that logic (logos) is the preeminent appeal in Shakespeare’s rhetorically centered theater. If what’s being said or done isn’t logical, it is senseless. There is no place for the illogical or senselessness in a Shakespearean play or sonnet.

A Shakespearean character may be played like music. Mr. Shimerman elaborates on this concept by presenting the concept of upward/downward inflection. An upward inflection is a vocal technique used to allow the audience to follow the character’s argument during an extended or complex monologue, soliloquy, or even an aside. Simply put, inflection is making the voice go up in pitch on the final syllable of a word, so as to cue listeners that there is more to be said in coming dialogue. So, that’s what George C. Scott meant when he remarked that “emphasizing the right word” is what makes Shakespeare easy to understand and to perform, for him at least.hy

In this enlightening 2-hour and 40-minute webinar, Mr. Shimerman touches on several concepts that clarify elements of Shakespeare canon for audience members, theater directors, and actors. A few of these are the use of breath, “to punctuate ideas or indicate that the character has experienced a catharsis. The use of breath includes sighs, quick breaths, inspirations, and letting-goes.”

Importantly, Mr. Shimerman explains the pivitol Elizabethan notion of Chain of Being, a system of ethics through which the world is perceived. Grouped together, the Chain of Being includes birds and animals, sins, virtues, people of various types and associations, heavenly bodies, earth elements, and the like. The nearer the group was to God, the more laudable they were considered to be. A member of one category of being on a hierarchical ladder is often compared to a complementary member on a parallel ladder of hierarchy, such as the lion as king of the Jungle and Henry V as King of England.

In this instructive webinar, Mr. Shimerman address the use of the syllogism by The Bard, which is a line of reasoning “by which the mind perceives that from the relationship of two propositions (referred to as premises) having one term in common there emerges a new, third proposition. This third proposition commonly called a conclusion, which may be true or might be false. Here’s a syllogistic example for Shakespeare’s Timon of Athens:

Flavins: Have you forgotten me sir?

Timon: I have forgotten all men; then if thou grantst th’ art a man, I have forgotten thee.

Of all of the insightful lessons from Mr. Shimerman’s webinar, two I trust will remain with me:

1. Never say a line that you don’t understand. If you don’t understand the words being said, the listener won’t either.

2. When asked if being a competent Shakespearean was necessary to be a good actor, Mr. Shimerman responded by saying that whatever success he’s had as an actor can be attributed to the understanding of language that he gained through the study and practice of Shakespeare’s rhetorical theater.

Indeed, Shakespeare is not only a pinnacle of drama and character. Shakespeare is also a pillar in comprehending logic, motivation, and persuasion. The Antaeus Theatre Company is certain to offer such webinars in the near future and beyond. To be included on the Antaeus Theatre Company‘s contact list, dial (818) 506-5436 or visit antaeus.org.