The play by Pierre de Marivaux was first performed in Paris in 1732, ran for six performances and folded. Perhaps playgoers were outraged at the character, Léonide, a young woman calculatedly seducing two men and a woman concurrently. Or it may be that Marivaux’s attempt to illustrate an inherent flaw in the cultural shift toward rationalism irritated rationalist French intellectuals. Triumph of Love thus gathered dust for nearly two centuries until a French revival in 1912 and a second French staging in 1956, followed by multiple other productions, a Broadway musical in 1997 and in 2001, a movie. But the American theater world’s highest praise fell to Stephen Wadsworth and Nadia Benabid’s 1990 translation and Wadsworth’s adaptation of the play, debuting at the McCarter Theater in Princeton, N.J. in 1992. Boston’s Huntington Theatre Artistic Director, Loretta Greco, happily chose Wadsworth’s adaptation with which to thrill patrons asking for a classic. Touching with time-honored theatrical humor the endless human experience of conflict between emotion and reason, Triumph of Loveis a classic delight.

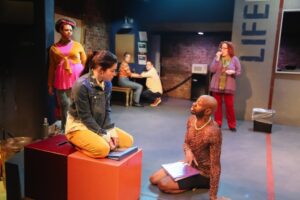

The traditionally complicated plot features Léonide (Allison Altman), a Spartan princess who with her maid, Corine (Avanthika Srinivasan), both dressed as men, has left home to insinuate herself into the household of the rationalist, anti-love philosopher, Hermocrates (Nael Nacer), and his equally rigid sister, Leontine (Mariana Bassham). Léonide has fallen in love with a handsome youth, Agis (Rob B. Kellogg), after glimpsing him as she walked in the woods. But Agis is the son of Cléomène, the former king of Sparta deposed by Léonide’s family. Agis has been raised by Hermocrates to despise Léonide as the usurper of a throne rightfully his. Her plan is to woo and marry Agis, thereby restoring him to the throne. But first she must outsmart both Hermocrates and Leontine while navigating meddlesome servants, the gardener Dimas (Patrick Kerr) and Hermocrates’ servant, Harlequin (Vincent Randazzo).

Arriving at Hermocrates’ garden, an understated, elegant three-tiered set of grass and manicured trees by Junhyun Georgia Lee, Srinivasan as Corine deftly explains the whole backstory to the audience and then serves throughout the play as voice-of-reason to Léonide’s amorous machinations. At first denied access to the garden, Léonide bribes Harlequin, Randozzo’s curious character in mask and motley also designed by Lee, standing in for the commedia dell’ arte tradition prior to 18th century theater and still overlapping it. Kerr’s Harlequin masterfully bears the weight of commedia dell’ arte humor, making the wordplay, occasional crudity, and antic movements feel somehow contemporary. As rational counterpart to Harlequin, Kerr’s Dimas at first feels flat in contrast to everyone else on stage, but gradually emerges as a contemporary Everyman. He’s the Greek chorus saying what the audience is thinking, sounding like some regular guy in line at a coffee shop, not like he’s acting. Which is probably the hallmark of a terrific. seasoned actor.

Constantly stymied in her intention to charm and then marry Agis, Altman’s Léonide constantly chooses to embody love as the only ploy or weapon available to her. In less skilled hands the character could be seen as merely manipulative and heartless, but Altman’s seduction, as a man, of the hidebound Leontine, is genuinely persuasive. And her appeals, as a woman named Aspasia (the name threaded through ancient Greek drama as that of an erotically adept courtesan and lateras an intellectual skilled at rhetoric) to the severely rational Hermocrates, feel real. Bassham’s Leontine, at first nearly a sexless cartoon “old maid” slowly transforms under Léonide’s influence to become lovely as a lover, a bit silly, a lot joyful. And Nacer’s Hermocrates, his lifelong philosophy shattered by Léonide’s passionate evocations of love, actually looks different as a lover. He’s lost the battle, yet he glows, proclaiming, “How weak we are! We are all so weak!” as he joyfully succumbs.

The story belongs to Léonide, and Altman flawlessly exhibits the charm, the passion and the savvy of perhaps the ideal 21st century young woman in the disguise of an 18th century young man. Quite an undertaking, and Altman nails it!

Of course all ends well, Rob. B. Kellogg’s Agis no longer an innocent boy but a kingly man as he and Léonide leave to marry. An elaborate floral piece overhead with raining petals, celebratory music by Fan Zhang, and a last shift in lighting by Christopher Akerlind of the clouds-in-sky backdrop reprise the romantic conventions of the original Marivaux play. It’s HEA all over again. Or is it?

Two figures remain standing side by side after everyone else has left, Leontine and Hermocrates. The fallen petals do not move at their feet, the music dims to silence. They don’t move but seem poised to speak, to deliver the obvious, final word on love and rationality. But they don’t, they are silent, and the curtain falls.

The Triumph of Love by Pierre de Marivaux. Translated and adapted by Stephen Wadsworth. Directed by Loretta Greco.

The Huntington Theatre, 264 Huntington Avenue, Boston, MA. 617 266-0800 huntingtontheatre.org

Through April 6, 2025